EPIC’s Carlos Lee talks to Ulli Hansen, co-founder and CEO of MSG Lithoglas

Could you tell us more about MSG Lithoglas – its history, technology, and applications?

Lithoglas was founded in 2006 in Berlin as a corporation based at Fraunhofer IZM to commercialise a unique technology capable of depositing glass at very low temperatures (below 80°C). It’s a very stable glass chemically and mechanically and we use it to apply thin glass films onto surfaces.

The main applications we thought of back then were not only surface passivation, but anodic bonding in MEMS products. Because the glass films deposited are highly transparent (in the visible range), optoelectronics was also a logical field of application for the technology.

When we started off in 2006, our operation was good for product development but not for high-volume production. In 2011, once we had our first volume product order from the automotive market, we needed our own production line. We started looking for venture capital, and successfully received funding to build our own production line in Dresden. Dresden does provide a very good base for this particular production line, because of its history and great links with the semiconductor industry. Also, Dresden can easily be reached from Berlin, where we still maintain our development site – it takes about two hours by car or by train.

How many people are currently employed by MSG Lithoglas?

We have almost 20 people across our two locations in Berlin and Dresden.

What is your background?

I have a MEMS background. I went to the Technical University of Braunschweig to study mechanical engineering with the target of majoring in microsystems technologies. That is more in the MEMS area, and I started working in Technology CAD software for MEMS processing after my diploma. That’s where I did my PhD on knowledge-based systems for technical CAD.

The work I performed on the software helped me to better understand the needs and the interactions of processing in semiconductors, especially MEMS, which is not standardised much. The lack of standards can result in the process flow becoming difficult because of incompatibilities (this is what the software at the time tried to distinguish or tried to predict). I think my knowledge on this helped me later on to have a broad overview on certain processes – helping to understand what can or cannot be done.

Did you work at Fraunhofer IZM at any point?

No. The glass deposition technology was originally invented at Schott, where I was previously employed. Schott worked with Fraunhofer IZM in the early 2000s to develop wafer-level packaging for image sensors, and I was part of that team. The glass deposition technology was part of this process flow.

Being a little bit early in the market, this development was stopped. However, the team agreed that it had a lot of potential – that’s when we had the idea of starting Lithoglas.

What challenges did you encounter in the start-up phase and what were the lessons learned?

One big challenge was establishing the next volume customer, despite receiving really good feedback from previous customers. Another difficulty was that it is not fast to go into production when you have a new technology. While we are not replacing any product directly with a novel technology, we are replacing a solution, which requires thorough evaluation and design.

Thus, the timeline was almost always longer than initially expected, which in turn required more money to get into production than we originally thought.

Another complication is that money in this field of work is not easy to find in Germany, so we really had a hard time with that aspect. That was one reason why some people from the original founding team left the company. In the end we were successful in securing the right investors (in Germany) for us, but there are only three founding members still with the company.

In addition, we discovered early on that having a great technology alone is not sufficient. We generated a lot of interest, and literally everyone we talked to had a new idea how to use this technology. So we were starting off in different directions and lacked a commercial focus. The marketing side of the business was more difficult than what we expected.

Having one technology that is novel and promising is a good starting point, but we often ran into situations where we were not able to fulfil the design and/or geometrical requirements of our customers. So, we broadened our portfolio of solutions to serve specific markets, from the MEMS realm to wafer- and diode-level packaging – essentially putting a strong focus on opto packaging in general.

Why does it takes time for customers to commit to incorporating your technology in their manufacturing process, despite the positive feedback?

Many of our customers incorporating our technology are sensor or emitter makers designing a new package for their devices. This involves testing the new packaging, and with the higher quality products that our technology enables, the testing just takes longer. If the new product is successful in testing and they are pleased with it, our customers still rely on their customers to put it in a module. So, our solution exists at the very beginning of the supply chain and it involves several steps that can be very time consuming, especially in automotive.

Whenever something in the supply chain goes wrong, even if it is not related to us, then the product may be stopped and all work is lost. That is a challenge from the very beginning – our customers need to make a package that will be built into something successful, and we must give our best to support them in all aspects possible.

What was your role when the company started in 2006?

I was an engineer and director of technical customer support. With a technology like ours, the sales can be very technological, so often you don’t talk with procurement persons but with the engineers.

The function of my job required finding a solution on how to fit the technology to the product of the customer. We had a different CEO with a financial background because, as technical people, we were lacking in that aspect. However, he left when we got venture capital. I became the CEO in late 2011 because I had the broadest knowledge in sales and also have a strong technology background.

What are the main aspects that you dealt with as CEO?

I was in charge of the financial part of the business once I took over before we hired some people and sourced things out. In the beginning, I also spent a lot of time in the cleanroom developing the products. But over the years, the sales part took more and more of my time. Yet I still sometimes visit the cleanroom to look into new developments, because it is important to know what is or is not possible with our processes. Also, it is essential not to lose that technical know-how for your processes, and to avoid promising something to customers that will not work.

In regards to the financial, engineering and sales aspects of the business, I am more involved in the sales part now. Of course, it is not only me. Worldwide we work together with representatives and consultants, but ultimately it all comes together at my desk.

They say that in the beginning it is the CTO who runs the company, followed by the sales person at some point, and then, when the company gets really big, it is the CFO who runs it.

Yes, that is true. I have a strong technology background, but then eventually I came out more into sales. Our CTO and I still maintain very close communications and are like best of friends in the company. Well, it has to be like that because in a high-tech business, it is important to maintain a close relationship between the technical development side and the sales side.

How do you see the company evolving in the next five years?

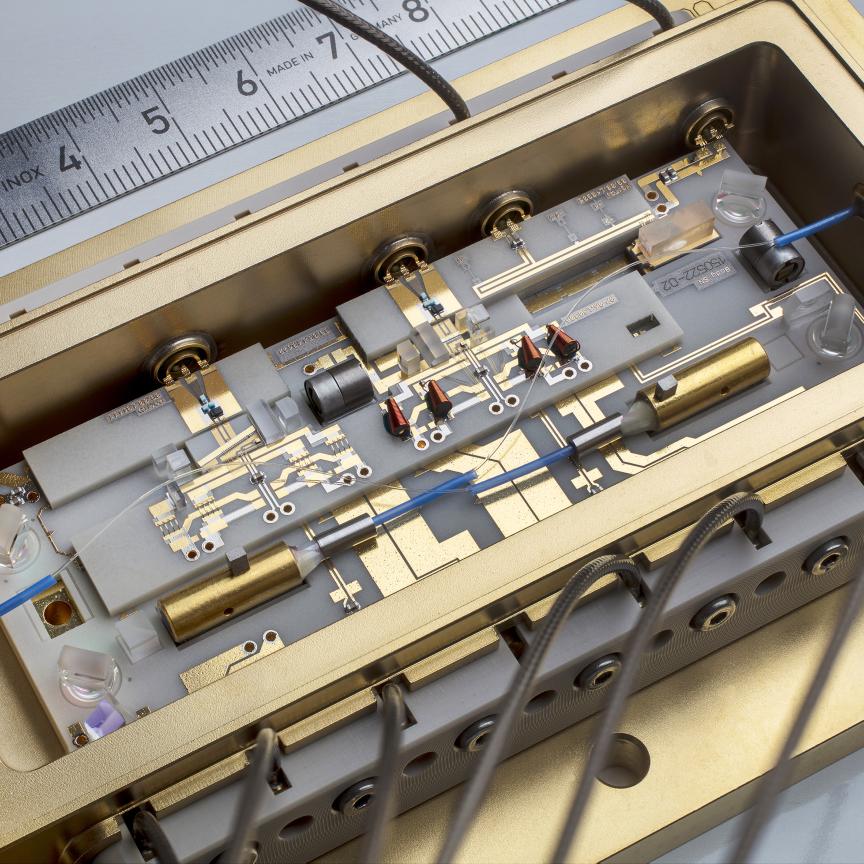

What we use our technologies for is to enable surface-mount technology (SMD) types of packages. Typically this involves miniaturisation and high reliability. Currently we are developing more and more into products for LEDs and lasers. We have a couple of ideas on how we can improve and add a higher level of integration to packages for laser diodes, which we are convinced will make a real difference in the market.

What advice would you give to young engineers starting up a business?

It’s in the mindset. In the first years I have sometimes wondered whether I would have been better off working for a larger company, which would allow me to take holidays whenever I want and not have to worry about finding someone to take on my duties whenever I take time off. This is something that you have to be prepared for when starting your own company. You must have the drive. You must be convinced that you have the right technology, the right product and the right team. Lastly, you should be willing to go the extra mile to get things done. If you do that and are successful, it is a very rewarding feeling to see that your own ideas are accepted and needed in the market.

Do not make the mistake of thinking that because you have a startup, you will get rich – and that should not be the major intention. It may happen in some cases, but the road will be difficult. Always be aware that things will take longer than expected – even if everything is going well. Choose your team well and be selective of your investors.

So, you have to make up your mind because it is not an easy route to take. However, it is a very rewarding path!